A new analysis of 100 contracts covering China’s financing arrangements with nations linked to Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative shows lending agreements that are unusually secretive, prioritize debt repayment to state-owned banks and are designed to bolster China’s position in the borrowing country.

However, the authors of “How China Lends” say, “Even when we find troubling terms in debt contracts between sovereign borrowers and China’s state-owned entities, we cannot conclude that they violate international standards: with few exceptions, such standards do not exist.”

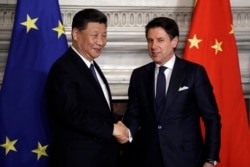

Launched in 2013 with much fanfare, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was designed as a network of enhanced overland and maritime trade routes to improve China’s links with Asia, Europe and Africa.

By 2019, China was signaling that it would modify the BRI deal in response to criticism about environmental risks, excessive debt and a lack of transparency in the financing of infrastructure projects.

What had looked like a good thing — improved infrastructure and the promise of economic benefits — left many nations unable to repay what they owed Chinese-owned banks and little recourse through internationally recognized agreements for restructuring their payments.

The analysis, a collaborative effort by the research lab AidData at the College of William & Mary, the Kiel Institute for the World Economy and the Center for Global Development, examined 100 debt contracts from China’s BRI projects and compared them with those of other bilateral, multilateral and commercial creditors.

“It does bring to light the fact that there are underlying strategic objectives that are taken into account by China before they undertake developmental lending,” said Shantanu Roy-Chaudhury, research associate at the Center for Air Power Studies in New Delhi. “The terms, therefore, can be used as a means rather than the end if a strategically important country begins to feel the pressure of mounting debt.”

Sam Parker, a researcher and a J.D. candidate at Georgetown Law who is a China subject matter expert for the State Department’s U.S. Speaker Program, told VOA Mandarin that the report confirms what scholars have long assumed and have been concerned about regarding Chinese loans.

“They lack transparency. They're tied to collateral. And overall, they make it harder for debtor countries to renegotiate or manage debt crises,” he said. “China is accumulating significant debts that look unlikely to be paid. I do not believe China purposely set out to entrap countries in debt, but it has nevertheless built leverage that it can use to acquire important assets or other geopolitical benefits. Debt book diplomacy (also called debt trap diplomacy) is a long-term process, but it is not a myth.”

Confidentiality clauses

The report reaches three main conclusions. First, “the Chinese contracts contain unusual confidentiality clauses that bar borrowers from revealing the terms or even the existence of the debt.”

The report finds that all China Development Bank contracts and 43% of contracts held by the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim Bank) include such clauses. Both banks are chartered to support official policy in industry, foreign trade, economy, and foreign aid.

According to Anna Gelpern, one of the authors and a law professor at Georgetown, confidentiality clauses put borrowers at a disadvantage.

“Let’s say a country has to default, and it approaches a creditor and says: ‘Can I delay repayment or have debt reduction?’ The first question from that creditor is: ‘What is everybody else doing?’ And the country’s answer is: ‘I can't tell you.’ The fact is all bilateral, multilateral or commercial creditors need to know how much debt you are exposed to,” she told VOA Mandarin.

Gelpern, an expert on sovereign debt and financial regulation,

added that confidentiality rules would limit a debtor nation’s ability to obtain loans from other countries other than China, increasing their dependence on Beijing.

Eyck Freymann, a doctoral candidate in China studies at the University of Oxford, said the confidentiality clause allows Beijing to exert its influence on these debt-distressed countries. His research focuses on why democratic countries engage with China's BRI, and how Chinese mega-projects influence their domestic politics.

“It looks shady and possibly corruptive,” he told VOA Mandarin. “It’s the sort of thing you would do if you are planning to do deals that would be controversial in the domestic politics, that you wouldn’t want opposition politicians, or the press, or the public to know.”

China first

A second point from the report is that these contracts require borrowers to prioritize repayment of their debt to Beijing or to Chinese state-owned banks ahead of other creditors.

“Close to three-quarters of the debt contracts in the Chinese sample contain what we term ‘No Paris Club’ clauses, which expressly commit the borrower to exclude the debt from restructuring in the Paris Club of official bilateral creditors, and from any comparable debt treatment,” the report said.

The Paris Club, founded in 1956, it is an informal group of creditor nations, including the U.S., “that have agreed to renegotiate and/or reduce official debt owed to them on a case-by-case basis,” according to the Congressional Research Service.

The debt contracts with China can lead to greater financial difficulties in the borrower nations and restrict their ability to develop, according to Gelpern. When combined with a confidentiality agreement, the borrowing nations become even more dependent on China.

And the No-Paris-Club provisions “predate and stand in tension with commitments China’s government has made under the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI)

(the “Common Framework”), announced in November 2020. The framework commits G20 governments to coordinate their debt relief terms for eligible countries.

The official bilateral debt of the poorest countries to G20 countries reached $178 billion in 2019, with 63% of the total owed to China, a World Bank study showed, according to Reuters.

Increasing influence

The report’s third point is that cancellation, acceleration, and stabilization clauses in these contracts potentially allow China to influence debtors’ domestic and foreign policies.

The report said that among the 100 contracts examined, more than 90 percent have clauses that allow the creditor to terminate the contract and demand immediate repayment in case of significant law or policy changes in the debtor or creditor country.

“This seems to be using the huge loans of the China Development Bank to safeguard China's extensive interests in the borrowing countries,” Gelpern told VOA. “I can’t say it is crazy or unheard of, but it is certainly on the far end of normal."

She added that rather than demanding the full payment, which the country probably doesn’t have, the lender would use its bargaining power to extract other kinds of concession. An example came in 2011 when, in exchange in deft relief, Tajikistan handed over 1,000 square kilometers of its land to China and “settled a century-old border dispute.”